Q&A

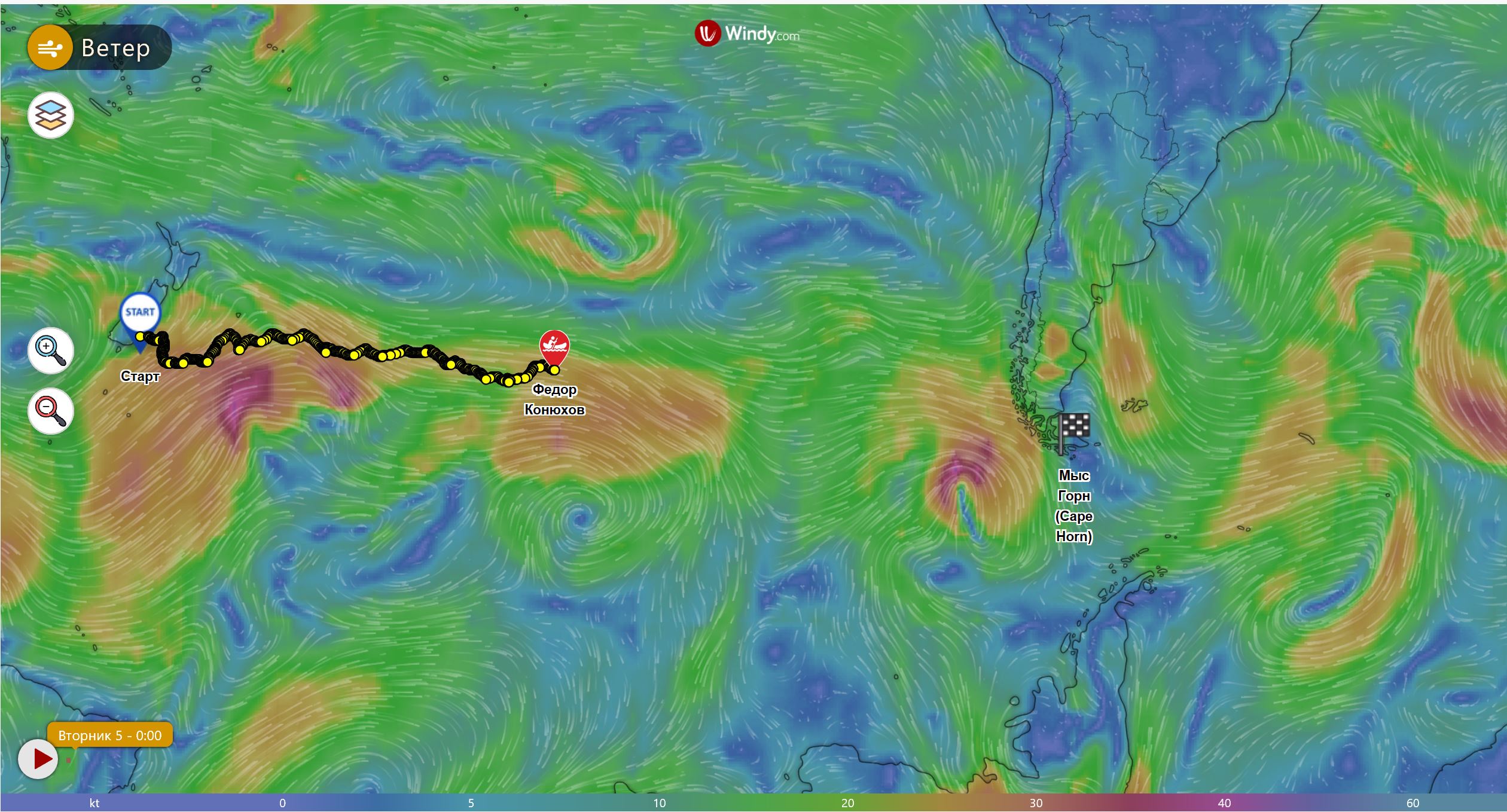

Fedor Konyukhov’s rowboat, the “AKROS” is approaching an important milestone – halfway. Having embarked on his journey on 6 December 2018 from the New Zealand city of Dunedin, the Russian explorer has rowed as far as the distance between Moscow and Lake Baikal – 5,400 kilometres. In this time, the Russian rower has set a number of records; the longest journey across the Southern Ocean in a rowboat – 62 days (the previous record was set by a Frenchman Joseph Le Guen– 59 days), with a greater distance travelled. Also, Fedor Konyukhov has celebrated his 67th birthday at sea, and is today the oldest solo ocean rower in the world.

OCEAN ROWS FROM AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND

(other than the Tasman Sea)

From New Zealand W – E (South Pacific Ocean)

| # | OCEAN ROWED | FIRST NAME | SURNAME | COUNTRY | BOAT | MILES | DEPART | ARRIVAL | DAYS AT SEA | FROM | TO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pacific W to E (Solo) | Joseph | Le Guen |

(France) |

Keepitblue.com |

1770 |

03/02/00 | 02/04/00 | 59 days | —–Wellington (New Zealand) | (Rescued) |

| 2 | Pacific W to E (Solo) | Jim | Shekhdar | UK | Ocean Challenge | 50 | 16/10/03 | 16/10/03 | 1 day | Bluff (New Zealand) | — (Towed back for rePairs) |

| 3 | Pacific W to E (Solo) | Jim | Shekhdar | UK | Hornette | – | 04/11/03 | 18/11/03 | 14 days | Bluff (New Zealand) | — (Picked up by Research Vessel Tangaroa) |

The Ocean Rows from Australia and New Zealand. As Compiled by Oceanrowing.com

Subscribers have been invited to submit questions for Fedor Konyukhov, and we have tried to compile them and have him answer them.

Check out Fedor’s the answers to the questions below:

Is there a lot of plastic and rubbish in the Southern Ocean?

FK: No, I haven’t seen any plastic in the Southern Ocean – not a single bottle or plastic bag – despite being so close to the surface of the ocean.

Is it true that the clouds above the ocean are different than the clouds above land?

FK: The clouds over the ocean are different, especially over the Southern Ocean. Lots of low cloud as this is a low pressure zone with constant cyclones.

How many storeys tall was the tallest wave you saw?

FK: I haven’t deliberately measured the height of the waves, but when I reach the crest I can see very far. It feels like I am on the captain’s bridge of a ship.

Are you scared?

FK: Any normal person is scared in such a boundless landscape and so far from civilisation. But I am used to it and know what to do in such situations.

Why are you doing this?

FK: This is how I live, this is my purpose in life – to explore our planet, myself and the world around me.

How does just one centimetre of hull withstand such conditions?

FK: The hull of the boat is made out of a composite “sandwich” (an external layer of carbon fibre, polystyrene and an internal layer of carbon). The underwater section of the hull is also reinforced with Kevlar, which is also used in bulletproof vests. So far, the boat has withstood the strain.

What happens if the boat capsizes?

FK: The boat is built to return to an even keel in the event that it capsizes. We deliberately conducted a rollover test in May of last year in England. However, we conducted the test without all of the equipment or antennae attached. Theoretically it should return to an even keel, but it would be better to avoid capsizing in these latitudes.

How do you dry your clothes?

FK: I don’t. The floor in the sleeping cabin is fitted with heating elements which are used in our houses and apartments. They heat the floor but do not dry my clothes. I have several different outfits packed in special bags. When clothes become soaked through and completely permeated by salt, I change them for a dry set. In the ocean, because of the salt water, it is impossible to dry clothes. You have to rinse it with fresh water first of which I have a limited supply.

How does the boat not get blown off-course during a storm?

FK: The boat is equipped with a rudder and autopilot. It keeps the boat at a given course. When the wind goes up to 25 knots and waves get up to 3 metres or more, I have to steer the boat as the wind and waves require. The course becomes secondary. The main thing is to survive the strong winds or storms. If there is a headwind the boat stays put or, if the headwind is too strong, I have to turn the boat around and lie at the opposite course. The main thing is not to have the boat facing starboard or port to the waves, to avoid a t-shaped impact.

Is there internet? How do you communicate?

FK: On board, I have two types of satellite communication from the company Iridium. There is a stationary telephone for voice communication, or I can send messages through Iridium GO. I should note that this year I’m testing out the satellite messenger Bysky. I can send messages from a smartphone like I’m using a regular, popular messenger, except photos haven’t been going through. The people at Iridium have been working on that issue. I call expeditionary headquarters every day in the evening Moscow time. If it’s storming badly, then we’ll exchange a brief SMS. I also read all of your messages and wishes.

What do you eat? What sort of rations do you have?

FK: I have special sublimated rations on board developed by the New Zealand company Radix. They were developed specifically for such projects. https://radixnutrition.com/

Do you communicate with passing vessels?

FK: Since the start I’ve only communicated with one vessel, and that was near the shores of New Zealand. I haven’t seen or heard anyone else in the ocean for 60 days. The radio is silent. It’s very unusual.

How do you withstand the pitching and rolling?

FK: The pitching and rolling is a constant problem. You can’t turn the ocean off. I’m constantly being tossed, raised over the waves, and pitched from side to side. The boat is constantly moving. Anyone with a weak vestibular apparatus or heart shouldn’t venture into the ocean in a rowboat.

How do you sleep?

FK: I get the sleep I need in 20-30-minute spurts. I can’t lie down and sleep for 7 hours. The boat would inevitably turn side-on to a wave. I always have to be on the alert and watching out for the direction of the wind and changes in the direction of the waves. The lack of sleep causes problems too, there is the danger that I might make a mistake, especially in stormy weather. Sometimes I forget to fasten my safety belt.

What sort of things do you think about while you’re on your journey? Have you been able to deeply contemplate anything?

FK: It’s all I’ve been doing – contemplating my life. Conditions out here are perfect for it. It seems to me that humanity is following the wrong path – a path that will lead to the destruction of ourselves and the planet. We create very little.

How many miles do you lose when drifting in a storm?

FK: If the storm is a tail-wind storm, then I continue along my course, but this is one of the problems with travelling through the Southern Ocean. There is practically never more than 3 days of favourable wind in a given place. For example, in the trade-wind regions the wind might blow from the Canary Islands to Antigua in one direction for a month; the wind, waves, and current will all move correspondingly in one direction. In the Southern Ocean, cyclonic systems circulate clockwise. If you are on a yacht, you can travel 300-500 miles a day, and move with a cyclone from West to East. But on a rowboat, due to your slow speed, the cyclone passes through you.

What sort of solar batteries do you have?

FK: Back in 2017 when survival systems were being developed for the “AKROS”, plans were made for three sources of generating energy: solar batteries, wind-turbines, and a fuel-cell (EFOY) system. I was very happy with how efficient the Russian flexible solar modules were. They were developed by the Research and Development Centre of thin-film technologies in the energy sector by the company TEEMP (www.teemp.ru). They basically superseded any need for other sources of energy. There is always a favourable power balance on the boat. The wind turbine also turned out to be the most useless of the energy sources. When the ocean is calm and the wind doesn’t blow faster than 15 knots, the wind-turbine doesn’t charge the batteries, and when the wind blows 25 knots or more, large waves are raised and the boat is tossed from side to side, making the use of a wind turbine downright dangerous. The boat’s designer, Phil Morrison also recommended removing the wind turbine in stormy conditions. If the boat capsizes due to a wave, the turbine will hinder the boat’s ability to return to an even keel. The total power of the photoelectric fuel cells installed on the “AKROS” is 720 watts. They power the navigational equipment, satellite communications, as well as water de-salination and cabin pumping systems.

Do you catch anything out of the ocean?

FK: Although I have fishing rods and lures, I haven’t caught a single fish. But I have caught calamari. In two months, I have caught 10 calamari. I catch them at around sunset using a fluorescent lure, and it is a gastronomic celebration for me.

What organisation registers oceanic crossings in rowboats?

FK: Similar to FAI (First Article Inspection) registering all records and achievements in aeronautics, the ORS (Ocean Rowing Society) in London tracks and registers all oceanic rowing journeys. The ORS receives data directly from satellite trackers and keeps its own map of my course. http://oceanrowing.com/Konyukhov2018/dist_map.htm